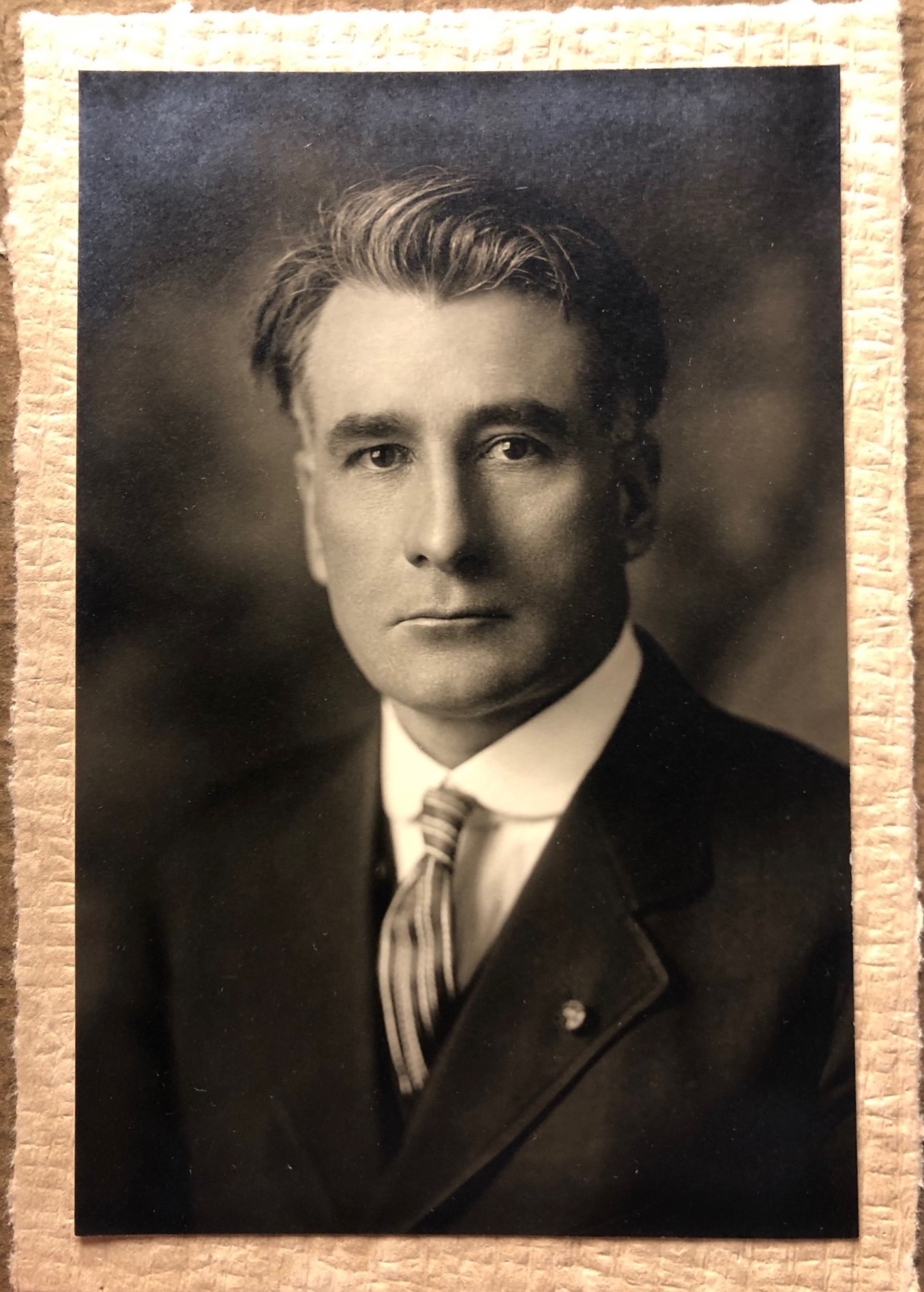

Melvin Gilmore: his work on Arikara Ethnobotany

Melvin Gilmore (1868-1940) was a pioneering ethnobotanist who wrote over 90 publications with a focus on recording the ethnobotany of 11 Native American tribes of the central US. He studied, published and recorded field notes on plant us by the Arikara, Dakota, Lakota, Ojibwe, Omaha, Osage, Oto, Pawnee, Ponca, Potawatomi, and Winnebago, producing a series of work that is foundational to Native American ethnobotany. Full records of the work cited below can be found in the Gilmore Bibliography.

Gilmore’s work was influenced by his childhood. Born in Valley, Nebraska, Gilmore grew up on a farm near the last Pawnee villages where people still lived in earth lodges. His childhood home was also in the vicinity of the recently created Omaha and Winnebago Reservations. Growing up, and during his time at Cotner College in Lincoln, Nebraska, he developed his interest in native culture and native plants. As he saw tribes being moved to reservations, he saw the loss of tribal lore and traditional ecological knowledge important to their traditional lifestyles. It became his life’s work to record this knowledge before it was lost forever.

While working as a curator at the Nebraska Historical Society, he earned his Master’s degree from the University of Nebraska studying the ethnobotany of the Omaha, which was published four years later (Gilmore 1913). In 1914, he completed his Doctoral degree at the age of 46, which resulted in his most well-known work “Used of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region”, published a few years later by the Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of Ethnology, and republished many times since (Gilmore 1977).

Gilmore developed strong relationships with the tribes and elders he researched. In 1914, Gilmore invited White Eagle, a Pawnee elder, who was living on the Pawnee Reservation in Oklahoma, to visit and document abandoned Pawnee villages in east-central Nebraska. White Eagle gave Gilmore the name “Pahuk” [Paahaku], meaning “Hill on the Water”. Paahaku, is also the name of a bluff overlooking the Platte River, a site scared to the Pawnee said to be the location of a mystical lodge where animals would hold council.

Gilmore became the curator of the North Dakota State Historical Society andhe developed an abiding interest in the Arikara, who were formerly part of the Pawnee. Through the next seven years, he formed relationships with the Arikara elders, learning about the old ways, interviewing them about their culture use of plants and other natural products The men and women he interviewed became the voices for the Arikara culture, and they sparked his keen interest to learn more.

After Gilmore took a position in 1923 at the Heye Museum (now part of the Smithsonian Institute), in New York City, he would return to visit the Arikara, first by train then by auto, to continue recording the lore of the Arikara. He often camped at the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota and wrote his anthropology friend and colleague George F. Will Sr. about his July 10, 1923 visit:

I have seen a number of my people and have sent out word to others. Everything seems to be favorable and I hope to get some results. In fact I have already today picked up a few new items of information. Snow says she is willing to make the baskets for me. I have seen Mrs. Red-tail and she says she will go out and get some clay and do the pottery for me. I have heard of some who can make bulrush matting. Claire Everett says White Bear can make a fish trap if I want him to. Red Bear told me about a number of articles. One of these is a deer decoy call made from bark. He says he will make it for me. Before I had been in camp long enough to go and gather wood for my fire Bear’s Belly came driving up to my camp with some wood and, though he can speak no English he made me understand the wood was for me” .

Will Family Papers, North Dakota Historical Society

When he met Native people he wanted to learn from , Gilmore visited with them and gained their trust. This work was often slow and time-consuming. From his written notes while visiting the Arikara on July 24, 1928, he stated:

I could not seem to accomplish much today. In the morning I wrote a report to Mr. Heye. Then I went up to see Mrs. Redtail about the pottery work, but there was no one there to interpret for us. She seemed anxious to do whatever she could. She got some clay out and broke up some stone for tempering, and then she kneaded the clay and pounded stone for me to see. She sent a small boy running to bring a schoolgirl from a neighbor’s place over the hill. But the girl was not able to talk much. Mrs. R said she would go after the Deanes to come over and interpret, and could come back at 6pm. So I came back to camp and got dinner, then I went over to Everett’s, but I found him away and his mother sick, and Mrs. Sittingbear gone visiting. So there was nothing to do there. I came back to camp and ate a cold lunch to make ready to go back to Redtail’s. When I got there I found Mrs. Redtail anxious again because Deanes had gone to Elbowoods and were not yet back. After waiting till 7pm I started away, but before I had gone far the Deanes arrived and called me back. But it was too late to start in now, so it was agreed I should come back in the morning and the Deanes’ older daughter would be there to interpret .

Will Family Papers, North Dakota Historical Society

Gilmore leveraged funds from the Heye Museum to pay his Arikara collaborators for cultural items such as pots, baskets, tools, bags, parfleches, bows and arrows, and moccasins, often created specifically for the museum. He also collected traditional dried foods such as chokecherries (Figure 2) and wild plums (Figure 3), teas , and plants used in ceremonies. These, and other significant culture artifacts are now part of the Smithsonian Institution collections. Gilmore was particularly interested in children’s games, which he recorded from the Arikara and other tribes. He believed other Americans should adopt such games in order to connect people with their bioregion and natural environment.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Wild Plums (Prumus americana)

Gilmore was a careful researcher, and focused on correct identification of plants. For example, in his notes taken on the Ft. Berthold Reservation in 1923, he recorded the following:

“The Arikara name of the ‘fish medicine,’ which until further identification I believe to be is now identified as Actaeaarguta Nutt., is skanikaatit.”

This later strike-through shows his repeated work on the manuscript and his careful attention to identification. Forty of his herbarium vouchers remain at the University of Michigan Anthropology Department (two document Arikara plants, the rest are from his Lakota work). In viewing his specimens, almost all appear to be identified with the correct names used in his time.

One important Gilmore publication (1931) on Arikara ethnobotany was “Notes on the Gynecology and obstetrics of the Arikara Tribe of Indians”. This article was based upon interviews of Arikara women, including the elder SteštAhkáta“Yellow Corn Woman”, also called Snow, who was 83 when he interviewed her in 1923 about issues related to childbirth and gynecology. According to SteštAhkáta “in olden times complications of pregnancy were uncommon.” This was due to many factors, including the skill of the midwives, such as SteštAhkáta. The willingness of the Arikara women to share details of their practices with a man is remarkable, and was based on the deep relationship Gilmore formed with the Arikara.

Although Gilmore produced over 25 publications containing Arikara cultural content, many of his notes were never published. As Gilmore began work at the University of Michigan, he had a series of illnesses, and was eventually diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. As his health declined, he could not even complete a trip back home from a visit to the Arikara in 1934, as a serious bout of illness left him in Fergus Falls, Minnesota unable to drive any further. His understudy, Volney Jones, had to drive up to Minnesota to rescue him and return him to Ann Arbor, Michigan where he could convalesce from what would be his last Arikara visit (correspondence with George F. Will, Sr., Box 1, Melvin R. Gilmore Papers).

One of Gilmore’s greatest regrets was that he could not complete the Arikara work in North Dakota. As he stepped down from his faculty position at the University of Michigan, he pleaded with long-term friend and seedsman, George Will of Bismarck, ND to finish his Arikara work. Will’s company started by his father, the Oscar H. Will and Company made native plants and new varieties of Native American corn available. At Gilmore’s request, Volney Jones sent George Will his most important materials, noting that it would take considerable effort to complete the work that Gilmore, unfortunately, could not due to his health. Regrettably, Will did not complete and publish the materials Gilmore sent him. Today, it is this work which we have undertaken, the completion and interpretation of Gilmore’s ethnobotanical notes not only to honor Melvin Gilmore, but especially to honor the Arikara people who shared their intimate, and profoundly insightful, traditional ecological knowledge.